Printing Office Shelter Architectural Report, Block 18 Building 12J Lot 48Originally entitled: "A Structure in Which to Interpret Papermaking in Colonial Williamsburg Printing Office Site, Block 18, Building 12J"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1421

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

A STRUCTURE IN WHICH TO INTERPRET PAPERMAKING AT COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURGPrinting Office Site, Block 18, Building 12J

Department of Architectural Research

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

March, 1987

The purpose of the open shed behind the Printing Office is two-fold: to provide protection for Crafts Department demonstrations of papermaking and to begin the introduction of relatively ephemeral hole-set buildings into the Williamsburg Historic Area.

The structure was designed by Willie Graham and myself in 1982, drawn by Willie Graham, and built by Roy Underhill, Mark Berenhausen, and Bill Weldon.1

Tubs, forms, and a press are sheltered by the building, and the top of the press is wedged between two joists. Demonstrations continue to be carried out here in warm weather.

We assume that there were quantities of buildings without foundations in eighteenth-century Williamsburg, as there were elsewhere in the Chesapeake region, although it is only since the 1950s that archaeologists have begun to recognize their footprints.2 A newly discovered Williamsburg example is a hole- 2 set blacksmith shop directly behind Shields Tavern. In addition, the rear wall of what was probably a granary at the Peyton Randolph site was supported by some sort of earth-fast posts. In order to present a more broadly realistic portrait of the eighteenth-century town, we think it beneficial to introduce structures such as this, however difficult it is to document specific examples.3

The form of the papermaking shed resembles that of open cart sheds surviving in England4 and, to less degree, attached sheds in the Chesapeake. Its details owe more to the latter.

Essentially, the building consists of a conventional eighteenth-century Virginia roof constructed of pine scantling and supported by unhewn locust posts. The posts are skinned and lightly squared at the upper ends, where tenons are set into mortises in the hewn and pit-sawn plate. The particular character of the posts and plates is based on the Vineyard tobacco barn in St. Mary's County, Maryland, and the early nineteenth-century sheds attached to work or production buildings 3 in southern Virginia and North Carolina. Examples include the Barrett, Rich Neck, and Eppes smokehouses in Southampton, the Kitchen barn in Isle of Wight, and the smokehouse and granary at the Finton Ferguson farm in Hertford County, North Carolina.5 We considered using braces like those at the earth-fast Vineyard barn and Chaney tobacco barn in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, but omitted them to reflect an expense-saving choice seen in most of the small buildings.

Joists are on approximately 2' centers and are half-lapped into the plates, following the most common pattern among surviving Chesapeake buildings. Also following a conventional approach, the rafters are butted and nailed to 1"-thick false plates set on the ends of the joists. For rafters, we used skinned pine poles lapped and pegged at the ridge. The end rafter collars are skinned poles half-lapped and pegged to rafters; the rest are riven boards butted and nailed to their rafters. The specific prototypes for the roof were the first and second-period rooms at Wall Store, a rural Lunenburg County building investigated during fieldwork for the Greenhow Store design. Since then we have seen pole rafters in the Bayside Farm bulkhead, St. Mary's County, Maryland; Whaley granary, Berlin, Worcester County Maryland; Woodstock Hall kitchen, Albemarle County, Ells Hill barn, Nelson County; Wilson tobacco barn, 4 Calvert County, Maryland; and the Vineyard tobacco barn.

The gable studs are skinned poles lapped to the end joist and butted to the rafters, following the details at Wall Store and the Vineyard barn.

For the roofing, we used sawn weatherboards rather than clapboards, with a feathered joint at the center, based on an original wrought-nailed roof at the Rochester House in Westmoreland County. Similar roof covering survives in the log granary at Foursquare in Isle of Wight County, although it was apparently never exposed to the elements. The same weatherboards were used on the gable ends. Tapered but unbeaded bargeboards were used and fascias were omitted. The use of unbeaded siding and bargeboards, both wrought nailed, has recently been observed at the Fairfield outbuilding in Henrico County.

Several points should be observed in retrospect. Most open shelters were probably much inferior to this. We were limited by the absence of information about skimpier structure and were partly constrained by the circumstances of practical use in the Historic Area. Nevertheless, less well-built structures should be added in the future. We felt that weatherboards were an interesting choice for roof covering and that they introduced some much-needed variety into the Historic Area. However, riven clapboards would probably be a more realistic (and now more 5 expensive) choice. Were we to do another shed, we would omit at least every other joist, as was done in the south shop at the James Anderson site. The finish of the joists might also be less extensive, perhaps being hewn on two sides (as proposed for House 1 at the Carter's Grove quarter) or on the top only, as was done at the Wilson tobacco barn. Further, most lapped joinery in roofs is nailed rather than pegged--as at the Whaley granary, Woodstock Hall kitchen, and Pruden milkhouse in Isle of Wight County--and this would be more believable. A structure of this character would also have little or no numbering for frame assembly, and certainly all the numerals should not face the side where the public stands. Finally, bargeboards probably should be omitted, as they are on all clapboard-sided buildings we have seen in the countryside.

Papermaking shed during construction. View from the southeast. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Papermaking shed during construction. View from the southeast. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Papermaking shed. View of the front posts, plate, joists and roof weatherboards. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Papermaking shed. View of the front posts, plate, joists and roof weatherboards. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Papermaking shed. Roof during construction, from the north. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Papermaking shed. Roof during construction, from the north. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

The Vineyard Tobacco Barn, St. Mary's County, Maryland. Section of the barn. Photo: Chappell, 1981.

The Vineyard Tobacco Barn, St. Mary's County, Maryland. Section of the barn. Photo: Chappell, 1981.

The Vineyard Tobacco Barn. Posts, braces, and plate of early addition, after partial demolition. Photo: Chappell,

1981.

The Vineyard Tobacco Barn. Posts, braces, and plate of early addition, after partial demolition. Photo: Chappell,

1981.

Barrett Smokehouse, Southampton County, Virginia. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Barrett Smokehouse, Southampton County, Virginia. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Barrett Smokehouse. Detail of porch post, plate, and rafter end. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Barrett Smokehouse. Detail of porch post, plate, and rafter end. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Barrett Smokehouse. Side view. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Barrett Smokehouse. Side view. Photo: Chappell, 1982.

Kitchen Barn, Isle of Wight County, Virginia. The freestanding post on the left is a recent replacement. Photo: Chappell, 1983.

Kitchen Barn, Isle of Wight County, Virginia. The freestanding post on the left is a recent replacement. Photo: Chappell, 1983.

Eppes Smokehouse, Southampton County, Virginia. Photo: Willie Graham, 1982.

Eppes Smokehouse, Southampton County, Virginia. Photo: Willie Graham, 1982.

Finton Ferguson Smokehouse, Hertford County, North Carolina. Photo: Graham, 1984.

Finton Ferguson Smokehouse, Hertford County, North Carolina. Photo: Graham, 1984.

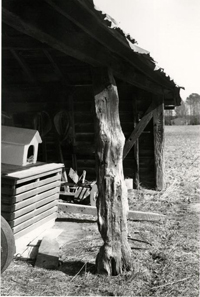

Kitchen Barn. Original porch post, worked only at the upper end. Photo: Chappell, 1983.

Kitchen Barn. Original porch post, worked only at the upper end. Photo: Chappell, 1983.